Our Land Acknowledgement is written in the context of our presence in the area – as researchers of its marshes and waterways – to recognize that much ecological knowledge precedes us; that people were on the landscape a very long time ago, making use of resources with knowledge about seasonality and life cycles of the biological and physical world around them, and with awareness of the interconnections and interdependencies among all “beings” that, like the People, persists today.

The Land Acknowledgement was developed in consultation with Paul and Denise Pouliot, Sag8mo (Head Male Speaker/Grand Chief) and Sag8moskwa (Head Female Speaker) of the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People[1], and using research into local Indigenous history that relied heavily on the work of Mary Ellen Lepionka.[2] We are grateful for their help and scholarship.

We invite you to join us in our learning process about the Indigenous history of the region as we describe each part of the Land Acknowledgment, and by exploring the links to related references and resources.

The Great Marsh and connected waterways and watersheds that we study are located on N’Dakinna (our homeland) of the Pennacook, Abenaki, and Wabanaki Peoples past and present, whose presence in and spiritual connection to the region date back over 12,000 years – well before the Great Marsh formed.

The Plum Island estuaries and their watersheds are located in the south-eastern-most portion of N’Dakinna, the ancestral homelands of the Pennacook-Abenaki Peoples. Using today’s geopolitical boundaries, N’Dakinna encompasses New Hampshire, and stretches from its southeastern boundary (northeastern Massachusetts), north into Canada, east into Maine, and west into Vermont[3], and is part of the larger Wabanaki (Dawnland) Confederacy homelands.[4] The southeastern portion of N’Dakinna is the region of the Mol8demak (Merrimack River), a major travel, trade, and resource corridor, connecting the uplands to the coastal area around Plum Island, including tidal marshes, estuaries, and the coastal ocean.

Map of N’Dakinna, defined in light green, with the state of New Hampshire outlined within. The general research area of PIE-LTER, in MA, is indicated by the location of Plum Island (map adapted from the Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective (INHCC) story map “Welcome to a land called N’Dakinna”.[5]

Before contact with Europeans, Indigenous communities of N’dakinna referred to themselves as Aln8bak (people or human beings). Tribal names were created by Europeans, who did not recognize complex and fluid Indigenous kinship relationships nor the Indigenous idea of belonging to the land, rather than owning it. The naming of kinship groups by the place they were encountered created false delineation among groups and territories and led to considerable confusion of conflating place names with the people living there, so the same people might be given different names if encountered in different places. For example, “The colonists variously called the native people living on Cape Ann the Agawam, Naumkeag, Pawtucket, Pentucket, or Wamesit, depending on where they encountered them on their [the native peoples’] subsistence rounds.”[6]

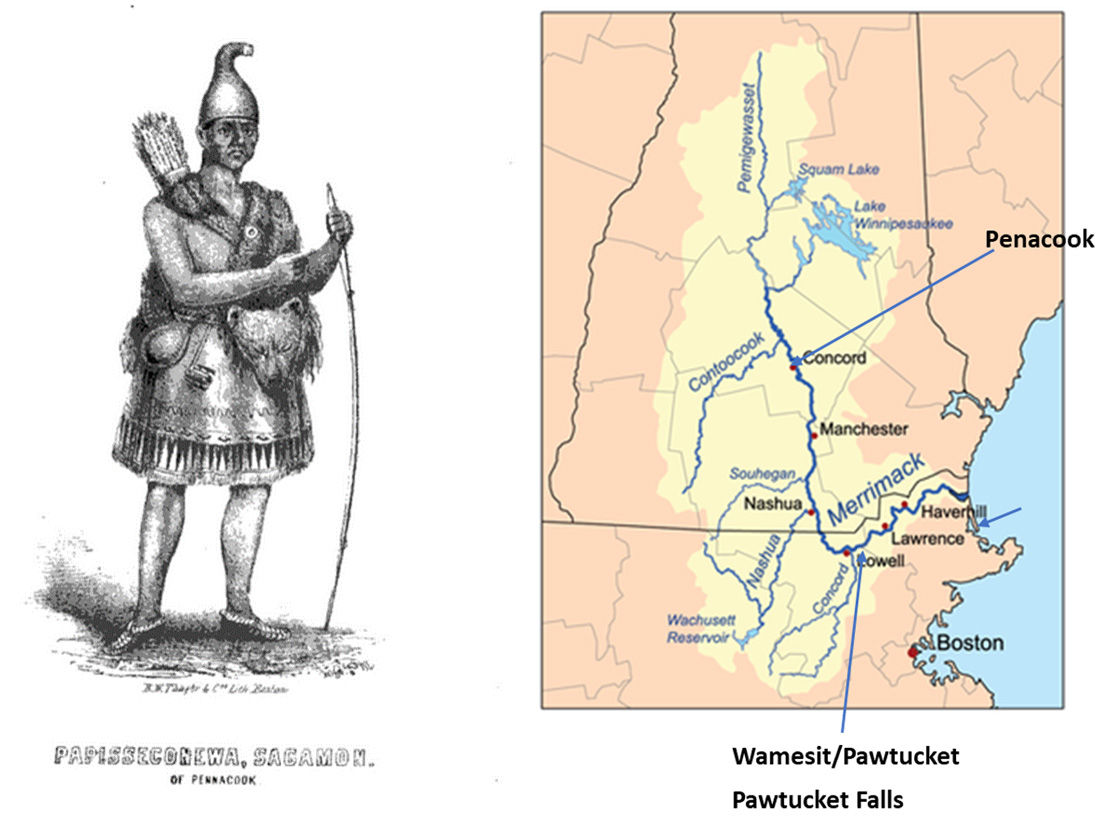

Pawtucket is often used for the kinship group and region of the lower Merrimack Valley and coastal region around Plum Island and Essex County to distinguish them from the Pennacook of the upper Merrimack. However, at the time of colonization, the many bands living along the Merrimack valley all paid tribute to the Pennacooks, and their Grand Sachem, Passaconaway (Papisseconnewa). The seat of Passaconaway’s confederacy was Penacook, today a part of Concord, NH, but for a time in the mid-1600s he resided at Wamesit and Pawtucket Falls (Lowell, MA) in winter, and at Agawam (Ipswich, MA) and Wenesquawam (Cape Ann, MA) in summer.[7],[8]

Recognizing the fluidity of these relationships and the colonial origin of many of these names, and on the advice of Paul and Denise Pouliot, we chose to use the more encompassing names of Pennacook-Abenaki and Wabenaki in our Land Acknowledgement.

Left: Representation of Papisseconnewa (Passaconoway), Pennacook Grand Sachem (Plate after p52 in Potter, C.E., 1856)[9]; Right: Merrimack River valley, showing seats of Passaconoway’s confederacy at Penacook (now Concord, NH), and his sometimes residence at Wamesit/Pawtucket Fall (near Lowell, MA), both sited along the river. (base map of Merrimack watershed: Wikipedia).

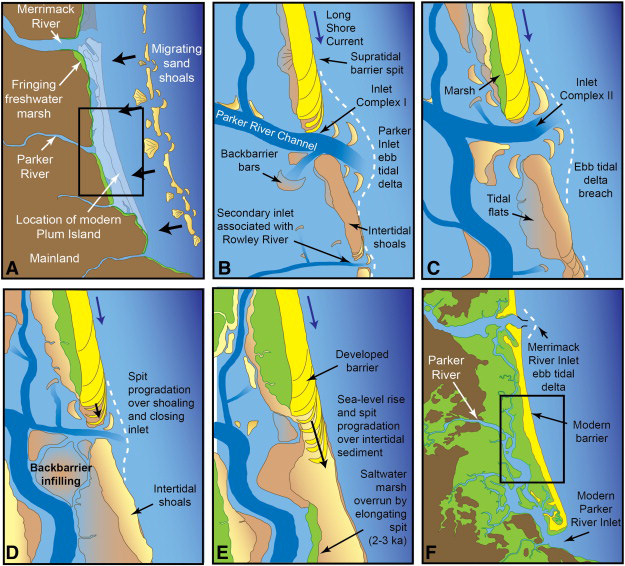

Archaeological evidence from the local area as well as regional sites confirm Indigenous People arrived on this landscape with the retreat of the glaciers, some 12,000 years ago. The largest PaleoIndian archeological site in the northeast, the Bull Brook site, is located in Ipswich, MA, near the mouth of current day Plum Island Sound. This site was a camp near where caribou were hunted at a chokepoint for caribou movement between Jeffrey’s Ledge (an island at the time, when sea level was ~60m lower than at present) and the mainland (absent marsh) which extended roughly 20 km further eastward.[10],[11] Dating of projectile points and other artifacts from the site indicate occupation of the site around 11,500 years ago. As part of research to map the formation of the barrier island that is now Plum Island, coastal geologists determined the formation of the salt marsh behind it – the Great Marsh- initiated 3,300 years ago, over 8000 years later.[12]

As the original stewards and ecologists of the aki (land), awan (air), nebi (water), olakwikak (flora), and awaasak (fauna), the alnôbak (people) knew and followed seasonal cycles of production, migration, and water flow - harvesting what they needed for food and shelter while managing land for growing crops and supporting game.

As the climate warmed and the landscape changed, Indigenous Peoples adapted their means of survival to match available resources and environmental stability. They shifted from a primary reliance on hunting large land and marine mammals, to incorporating fish and then shellfish taken from estuaries that formed, along with marshes, when sea level stabilized ~ 3300 years ago.[12] Fish and shellfish became a major source of protein. Flora changed as well, providing an increasing diversity of land plants, including many marsh and wetland plants, that were used for food, medicine, and fiber.

Shell middens testify to the intensive but sustainable use of shellfish by Indigenous Peoples along the Atlantic coast. Top: shell middle overtopped by soil, Ipswich, MA.[14] Bottom: Soft-shell clams, like these fragments from a shell midden on Spectacle Island, MA[15], are found in many shell middens around the marshes of Essex Co., where, in contrast to many other locations where oysters dominate, clams made up the bulk of shellfish harvests.[16],[17]

Cattails in the Upper Parker River. Left: leaves, stems, and flowers; Middle: roots and rhizomes; Right: seed heads and “fluff”. “One of the most notable and prominent wetland plants is the Cattail or Arrow Plant (Typha latifolia) or in Abenaki, Bakwaaskw. The whole plant, including the pollen, is used for various foods, medicines, and fiber materials.” - Pouliot.[18],[19]

Europeans would have encountered a People practicing lifeways that included permanent settlements along with seasonal migration between settlements, using a mixed economy that included agriculture and forest management (burning), and a recognition of seasonal scarcity and abundance.

“This cyclical seasonal movement between resource bases within an ecosystem, which functioned to enhance the diversity of the environment and to facilitate the survival of its many inhabitants, had been ongoing in the Wabanaki homeland for millenia.”

“Wabanaki people had developed an embedded knowledge based on longstanding resource use and reciprocal relationships of exchange with their human and “other-than-human” relations in this place.”[13]

This knowledge lives on in the alnôbak despite the dispossession of these lands and resources by colonialism. We honor Pennacook, Abenaki and Wabanaki Peoples, past, present, and future, and commit to support and include Indigenous environmental and educational initiatives in our work.

Descendants of Pennacook-Abenaki of the Merrimack region reside throughout N’Dakinna, within the Wabanaki Confederacy, and beyond, in a far-reaching diaspora.[1],[20],[21] Many may not be members of federally- or state-recognized tribes, but they are still here. With them resides thousands of years of traditional ecological knowledge about the natural environment and human beings’ place within it and responsibility to it, passed across generations through storytelling and other cultural practices.[13],[22],[23]

To honor our stated commitment, we will:

- Educate ourselves and help propagate Indigenous perspectives.

- Seek out opportunities for collaboration and to include Indigenous knowledge (IK), while respecting Indigenous rights to data and IK.

- Incorporate available educational resources into classes.[24],[25]

- Create opportunities for students.

In the face of climate change and so many environmental stressors, management and conservation efforts need multiple sources of knowledge and ways of knowing, as well as approaches to resiliency and adaptability. Indigenous knowledge and culture have much to contribute to western science, with areas of convergence including “local-scale expertise, climate history, research hypotheses, community adaptation, and community-based monitoring.”[22] To learn more, we encourage you to explore the work of Indigenous and other scholars and offer the additional resources below.

Additional Resources

“Greater Lowell Indian Cultural Association.” Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.greaterlowellnatives.com/.

Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective. “Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective.” Accessed February 21, 2024. https://indigenousnh.com/.

Pouliot, Paul, Svetlana Peshkova, and Caitlin Burnett. “Place-Names Divide Indigenous Communities in New England.” Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective (blog), July 20, 2020. https://indigenousnh.com/2020/07/20/place-names-divide-indigenous-communities-in-new-england/.

“The Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag.” Accessed February 21, 2024. http://massachusetttribe.org/.

Citations

[1] “Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People,” accessed February 21, 2024, http://www.cowasuck.org/.

[2] Mary Ellen Lepionka, “Preface: History of Cape Ann and Beyond,” Indigenous History of Essex County, Massachusetts (blog), June 27, 2023, https://capeannhistory.org/.

[3] “N’dakina - Our Homelands,” Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People (blog), accessed February 21, 2024, http://www.cowasuck.org/homelands.html.

[4] “Native Land Digital,” Native-Land.ca, accessed February 21, 2024, https://native-land.ca/.

[5] Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective, “Indigenous Cultural Heritage in New Hampshire,” ArcGIS StoryMaps, February 6, 2024, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/dff92ba07bac49af84f455f3ddac3ce6.

[6] Mary Ellen Lepionka, “Who Were the Pawtucket and Where Did They Come From?,” Indigenous History of Essex County, Massachusetts (blog), October 17, 2022, https://capeannhistory.org/index.php/who-were-the-pawtucket-and-where-did-they-come-from/.

[7] Mary Ellen Lepionka, “How Were the Pawtucket Organized and Led?,” Indigenous History of Essex County, Massachusetts (blog), accessed February 21, 2024, https://capeannhistory.org/index.php/how-were-the-pawtucket-organized-and-led/.

[8] Peter S. Leavenworth, “‘The Best Title That Indians Can Claime’: Native Agency and Consent in the Transferal of Penacook-Pawtucket Land in the Seventeenth Century,” The New England Quarterly 72, no. 2 (1999): 275–300, https://doi.org/10.2307/366874.

[9] Chandler Eastman Potter, The History of Manchester, Formerly Derryfield, in New Hampshire: Including That of Ancient Amoskeag, Or the Middle Merrimack Valley; Together with the Address, Poem, and Other Proceedings, of the Centennial Celebration, of the Incorporation of Derryfield; at Manchester, October 22, 1851 (C. E. Potter, 1856).

[10] Mary Ellen Lepionka, “Who Were the Paleoindians?,” Indigenous History of Essex County, Massachusetts (blog), accessed February 21, 2024, https://capeannhistory.org/index.php/who-were-the-paleoindians/.

[11] Brian S. Robinson et al., “Paleoindian Aggregation and Social Context at Bull Brook,” American Antiquity 74, no. 3 (July 2009): 423–47, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0002731600048691.

[12] Christopher J. Hein et al., “Refining the Model of Barrier Island Formation along a Paraglacial Coast in the Gulf of Maine,” Marine Geology 307–310 (April 15, 2012): 40–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2012.03.001.

[13] Lisa T. Brooks and Cassandra M. Brooks, “The Reciprocity Principle and Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Understanding the Significance of Indigenous Protest on the Presumpscot River,” International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies 3, no. 2 (January 2010): 11–28, https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.389399112571305.

[14] Mary Ellen Lepionka, “How Did the Eastern Algonquians Make Their Living in Essex County?,” Indigenous History of Essex County, Massachusetts (blog), accessed February 21, 2024, https://capeannhistory.org/index.php/how-did-the-eastern-algonquians-make-their-living-in-essex-county/.

[15] “Archaeological Exhibits Online - Massachusetts Bay,” Massachusetts Historic Commission (blog), accessed February 21, 2024, https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcarchexhibitsonline/massachusettsbay.htm.

[16] Leslie Reeder-Myers et al., “Indigenous Oyster Fisheries Persisted for Millennia and Should Inform Future Management,” Nature Communications 13, no. 1 (May 3, 2022): 2383, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29818-z.

[17] Mary Ellen Lepionka, “Algonquian Shellfish Industries on Cape Ann,” Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 78, no. 1 (2017).

[18] Indigenous NH Foodways & History, n.d.

[19] Robin Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (Milkweed Editions, 2013).

[20] Mary Ellen Lepionka, “Living Descendants of the Native Americans of Agawam,” Historic Ipswich (blog), October 21, 2022, https://historicipswich.net/2022/10/21/living-descendants-of-the-native-americans-of-agawam/.

[21] Alvin Hamblen Morrison, “Dawnland Diaspora: Wabanaki Dynamics for Survival,” Algonquian Papers-Archive, 1998.

[22] John J. Daigle et al., “Traditional Lifeways and Storytelling: Tools for Adaptation and Resilience to Ecosystem Change,” Human Ecology 47, no. 5 (October 1, 2019): 777–84, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-019-00113-8.

[23] Fikret Berkes, Sacred Ecology (Routledge, 2017).

[24] Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective, “Our Educational Resources,” December 6, 2019, https://indigenousnh.com/educational-resources/.

[25] “Wabanaki Youth in Science,” Wabanaki Youth In Science, accessed February 21, 2024, https://www.wabanakiyouthinscience.org/.